A hero for defeating ISIS, Iraq's PM still has to woo voters

Iraqi

Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi during a visit to Mosul after Iraqi and

US forces wrested control of the city back from the Islamic State.

(CNN)In the years before the 2003 invasion, Iraqis only had one choice at the poll: Saddam Hussein.

Fifteen years later, the tyrant deposed and executed,

Iraq's field of candidates for elections on Saturday is now so varied

that voters can choose between thousands of Shia, Sunni and Kurdish

aspirants from 87 parties.

With

so many contenders this year, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi stands at

the epicenter of the hotly contested election. And though he's

universally considered a hero for routing ISIS, his victory at the polls

is far from certain.

Iraq's PM claims Mosul liberated from ISIS 02:01

It's been a tumultuous four years for Abadi.

He was appointed prime minister in 2014 after his predecessor oversaw a whiplash-inducing retreat of Iraqi soldiers in the face of an ISIS assault on one of the country's largest cities.

Since then, he's stood at the helm of an eventual defeat of the Islamist group, put down a Kurdish rebellion in the north,

and hosted Iranian and American forces within elbowing distance of each

other without it devolving into another all-out war on his turf.

Meanwhile,

suicide bombings continue to plague Baghdad, disputes over oil revenues

have stalled in parliament, and more than two million Iraqis remain

displaced from the war with ISIS.

Now, Abadi faces a reckoning by the people, as Iraqis go to the polls on May 12 to vote in a new parliament.

A fractured coalition

Notwithstanding the myriad challenges facing a decimated Iraq -- the government estimates it will need around $90 billion to rebuild cities

and towns left in tatters by the Islamic State -- Abadi has had to

navigate his way to building new regional alliances with his

predecessor, Nuri al-Maliki, continually nipping at his heels.

Maliki,

who has stridently attacked Abadi's Western leanings by insisting

Iraq's truest ally remains Iran, has broken from the prime minister's

bloc and created his own.

In the 2005 elections, the first real vote following the ouster of dictator Saddam Hussein,

Shia political parties ran as a single group. That was both to ensure a

Shia victory for the first time after years of Sunni dominance, and

consolidate power within the legislature to enact the laws they wanted

without having to woo other factions.

This

time, however, the Shia are split into five coalitions, and Abadi's

"Victory Alliance" list includes Sunni candidates in provinces such as

Nineveh in the north and Anbar to the West.

His is also the only one to

run in each of Iraq's 18 provinces.

An

official guides the hand of blind man Jawwad Shkeir, 56, as he cast his

vote on 30 January 2005, in the southern holy city of Najaf. The

elections were Iraq's first full vote since Saddam Hussein was routed

from power in 2003.

But despite the endorsement of allies including the US,

Abadi faces the likelihood of not gaining the necessary seats to win a

majority, which means he'll have to reach out to groups including

Maliki's and that of former Transportation Minister Hadi al-Amiri -- a

one time head of an umbrella group of Iran-backed Shia militias that

fought against ISIS.

The vote among

the Shia Iraqis will likely be split between those three groups, making

it nearly inevitable that Abadi will have to negotiate with them.

The Shia paramilitaries, known as the Popular Mobilization Units,

were condemned for their brutality against Iraqis living in areas that

were under ISIS' control. Human Rights Watch called on Iraqi commanders

to prevent the PMU from taking part in military operations, citing a

record of abuses against the Sunni population including summary

killings, enforced disappearances, torture and the destruction of homes.

In an interview in 2016

Amiri said: "I don't claim that there are never violations that occur

during war. This is a war, and in a war, there are violations."

Eventually,

the PMU were excluded from fighting campaigns in Sunni areas. The US

and Iraqi military led assaults into ISIS-controlled towns including

Mosul, to avoid inflaming sectarian tensions that arose when the PMU

fighters were sent in.

Playing the 'Victory' card

On December 9 last year, Abadi declared victory over ISIS.

He said Iraqi military forces had driven ISIS fighters from Iraq and

had secured the border with Syria.

The campaign to eradicate the group

took more than three years and encompassed US and allied troops on the

ground and in the air, including some 25,000 coalition airstrikes.

That

victory is Abadi's biggest political card in this election, hence the

name of his "Victory Alliance."

He also visited regions of the country

that had previously been in ISIS hands, promising to help residents

rebuild.

"He's the favorite to win,

and he's trying to pursue this Iraq-wide strategy," said Renad Mansour,

a research fellow in the Middle East and North Africa program at

Chatham House.

"He came to the Kurdistan region and he came to Sunni

areas in Nineveh and Anbar and now he's in the south, he's trying to

cover the whole country."

Speaking

to CNN from Iraq, Mansour said that the high that seized the nation

after the defeat of ISIS has quickly faded, and reality has set in.

The

issues that made Iraq a breeding ground for extremist groups, he argued,

still exist.

"People are like, we

beat ISIS, fine, but the leadership hasn't been able to deliver

anything to us, the system is corrupt and there's all these issues, you

have the same leaders promising change and promising to combat the

structure that they themselves built so you have a lot of Iraqis who

believe that not much change is possible through elections," he said.

Ambivalence, and Iran in the background

Many

Iraqis say they will not vote on Saturday because most of those running

are familiar faces who in the past promised change, but have failed to

deliver.

"When

you put one or two people in jail that doesn't mean you have fought

corruption," said political candidate Faisal Abdullah Obeid, speaking to

CNN in Baghdad, where he is running for parliament on a center left

platform.

"If you don't follow up on them all, the Iraqi people will ask you today or tomorrow what you've done for Iraq," said Obeid.

"We

can say honestly and with all transparency that the political class is

unqualified to rule the country, and we can say he was the best among

them, but we can't say he's answering the demands of the Iraqi people,"

Obeid said of Abadi.

As a sign of

how ambivalent people are about voting, the country's highest Shiite

religious authority, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, didn't insist

everyone get out and vote on the weekend. In the past he'd demanded

Iraqis take part to ensure a solid Shia showing at the polls.

In

a recent sermon, Sistani left the decision to vote up to the Iraqi

individual. But he has told voters to "avoid falling into the trap of

those ... who are corrupt and those who have failed, whether they have been tried or not."

"This

time, he said voting is part of the system but it's up to the citizen

to vote or not to vote, so very clearly he's disgruntled by the

political system in Iraq," Mansour said.

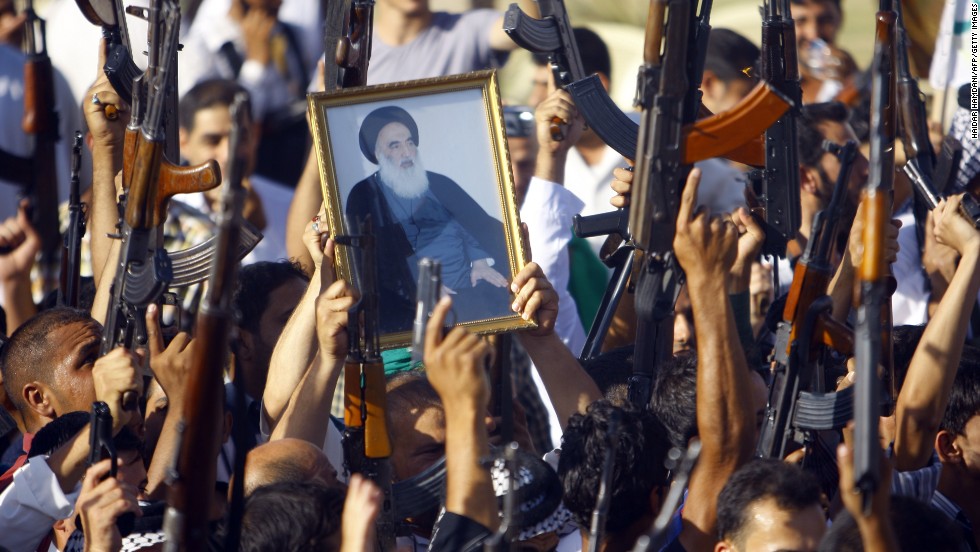

Iraqi

Shiite tribesmen brandish their weapons and a poster of Shiite cleric

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in June 2014, as they gather to show

their willingness to join Iraqi security forces in the fight against

militants who'd taken over several northern Iraqi cities.

The

danger for indifferent Iraqis is to continue to vote along identity

lines, even as the sectarianism that enveloped the country for so many

years now appears to be ebbing.

"The

voters always have the last word and could well decide to return to the

usual suspects, in the same political alignments, to parliament," said Douglas Ollivant, a former NSC director during the Bush and Obama administrations.

"Further,

it is not at all clear that this hoped-for diversity increases

stability, or in any way makes for a more functional or less corrupt

government once it is formed."

The

specter of Iranian dominance continues to overshadow Iraq, even as Abadi

has spent his time in office building alliances with Saudi Arabia and

beyond the Middle East, traveling to France, and even Japan.

"Iran is in a strong position," wrote Zalmay Khalilzad, a former US ambassador to Iraq in the Wall Street Journal.

"It

is not evident that Tehran has decided on its preferred candidate for

Iraqi prime minister. Major constituencies, including the dominant

Shiite Islamists, are divided.

Iran's apparent strategy is to support

several groups in the hope that it will be kingmaker in the bargaining

over the next Iraqi government."

President Trump welcomed Prime Minister Abadi to the White House in March 2017.

'Between a hammer and an anvil'

Rabih

al-Zubaidi, a health food store owner in Baghdad, still remembers what

it was like before the fall of Saddam.

Those days, he insists, were

better.

"We felt security, jobs

were available for the people, you could say life was good," he told

CNN.

"Right now there's corruption in the leadership and with the

politicians. I think the previous situation was better."

He points to high unemployment among the country's youth and endemic corruption within the economy that hampers entrepreneurs.

"If

young people want to start a business, the country fights them with

taxes, labor inspectors enforce more rules," he claims.

"Abadi is

between a hammer and an anvil, between the US, Saudi Arabia and Iran,

and don't expect him to succeed in doing very much."

Post a Comment